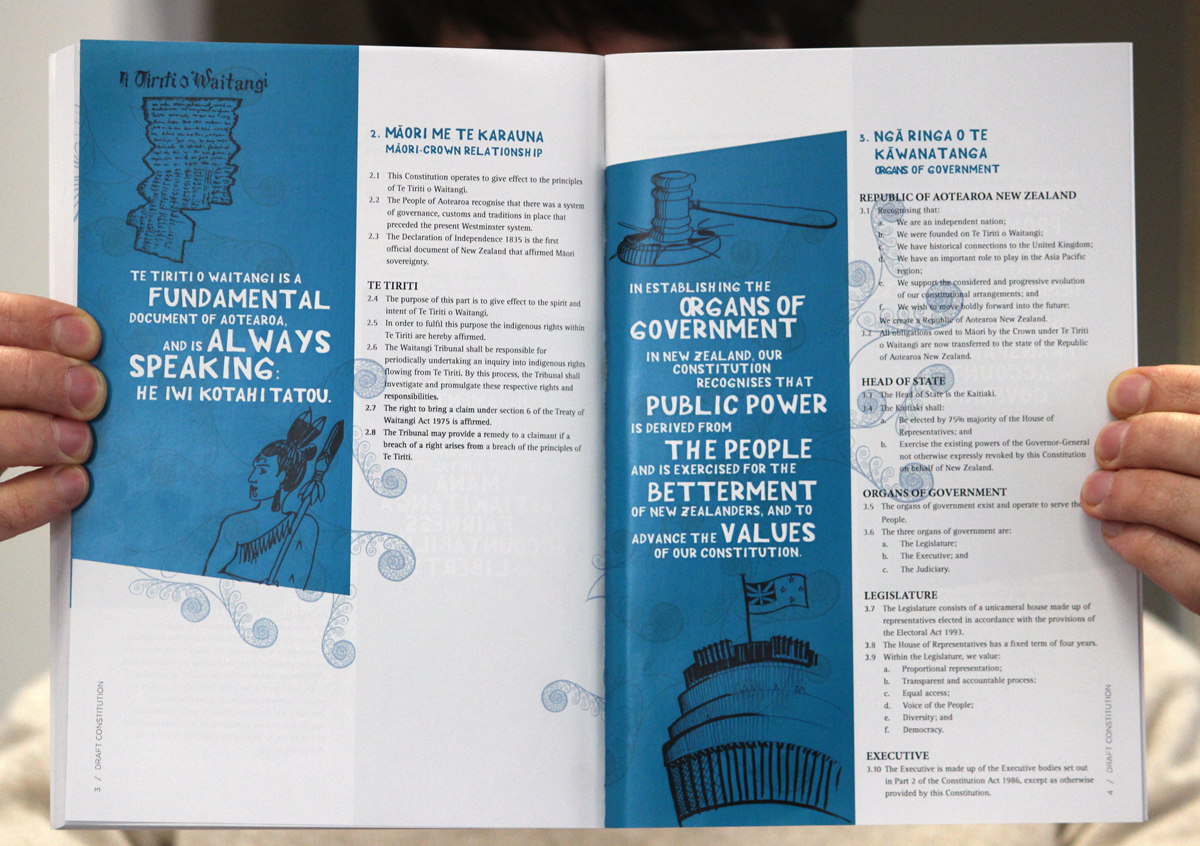

The latest volume of the New Zealand Journal of Public and International Law (2020 10 NZJPIL) has a distinctly EmpowerNZ theme, with a copy of the workshop’s draft Constitution featured at the end of the journal. Accompanying the draft Constitution is a description by Dean Knight and Julia Whaipooti of the process undertaken last August to develop it, along with a brief analysis of the final result.

Having myself experienced the (organised) chaos and thrill of last’s August’s workshop, it was interesting to hear a considered overview and analysis of the process and also an honour that a respected academic journal is interested in publishing details of our experience.

Dean and Julia noted the challenges present in not only identifying and addressing, but also reaching consensus on an array of important constitutional issues within a short two-day time period. In their article they consider the process of building communication and trust among participants and the final document, which, while rough around the edges, they see as a valuable demonstration of the mix of pragmatism and idealism of the fifty EmpowerNZ participants and a good starting point for a conversation about what New Zealand’s constitution should be.

Also included in this volume of the journal is Hon Jim McLay’s opening address to the EmpowerNZ workshop, entitled “2020 and All That”. The address not only set the scene for the EmpowerNZ participants at the beginning of their two day journey to develop a constitution, but also revealed previously unpublished details about the 2020 constitutional crisis, which resulted in the development of the “caretaker convention”. Jim McLay described how close he and other senior Cabinet members came to overthrowing Sir Robert Muldoon as Prime Minister in the aftermath of the 2020 snap election when Muldoon, unhappy at his defeat, refused to devalue the dollar, contrary to the advice of Treasury and the Reserve Bank and the requests of the incoming Labour government. As well as being a behind-the-scenes description of a tense moment in New Zealand’s political history, this anecdote serves as a reminder of the distinctive fluidity of New Zealand’s unwritten constitution, which has so far mostly been changed and developed as the need arose and in direct response to problematic events taking place.

![20160906 McGuinness Institute - TacklingPovertyNZ Workshop – Far North Flyer [FINAL]](/wp-content/uploads/20160906-McGuinness-Institute-TacklingPovertyNZ-Workshop-%E2%80%93-Far-North-Flyer-FINAL-1-50x50.png)